Ask any grizzled footwear historian about the most influential initiatives in Nike history, and one name you’re sure to hear is CO.JP. Running from the mid-‘90s into the ‘00s, CO.JP had humble beginnings as a set of store-exclusive makeups for Japanese retailers. However, it quickly morphed into its own Nike sub-label, which then spread beyond the island nation to set down roots in New York, London, Paris and more.

“CO.JP is the architect. If it wasn’t for CO.JP, you wouldn’t have quickstrikes, you wouldn’t have segmented distribution, you wouldn’t have Tier Zero releases, you wouldn’t have SNKRS.” – Jeff Staple

Short for “Concept Japan” and once the URL for Nike’s Japanese website, CO.JP paved the way for today’s collaboration-crazy world of footwear; the roots of everything from the “drop” model to the Nike SNKRS app can be traced back to it. “CO.JP is the architect. If it wasn’t for CO.JP, you wouldn’t have quickstrikes, you wouldn’t have segmented distribution, you wouldn’t have Tier Zero releases, you wouldn’t have SNKRS,” says Staple Design founder and longtime Nike collaborator Jeff Staple.

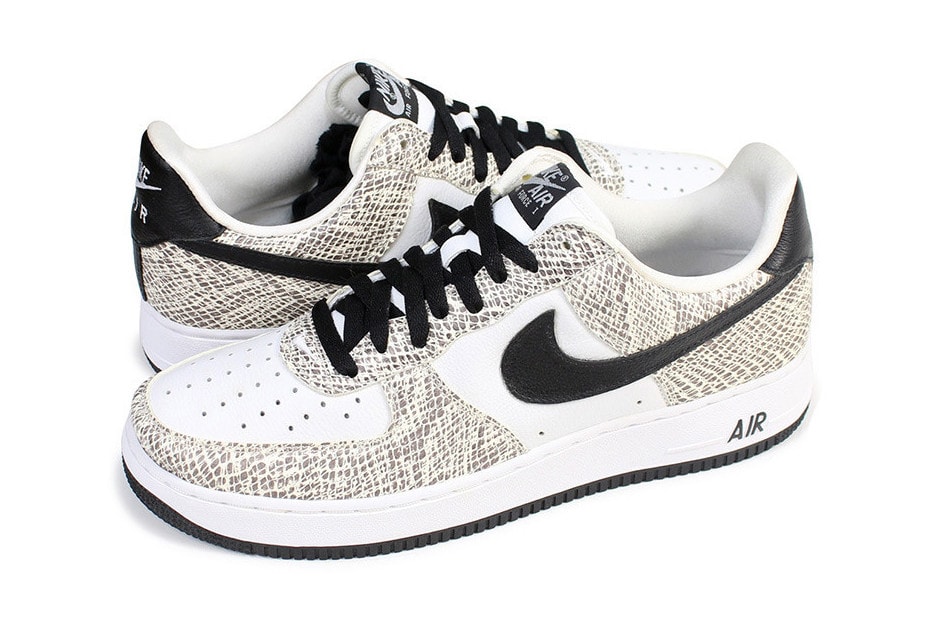

CO.JP releases read like a greatest hits list. There’s the Air Force 1 “Linen,” a crisp, summery sneaker that melds buttery tan leather with sweet pink Swooshes and the Air Force 1 “Cocoa Snake,” a luxurious reptilian style, both of which released in 2001. That same year brought the Air Jordan 1 “Japan Addition” pack, the first four non-OG Air Jordan 1 colorways to be released, whose runs were limited to either 2,001 or 3,000 pairs per style. Then there are ultra-rare Nike Dunks like the Pro B line, the precursor to Nike SB’s SB Dunk Low.

All of CO.JP’s astounding styles could fill a whole book. But take a look at any handful of releases and the line’s impact is immediately apparent, which is why CO.JP is spoken of in glowing, reverential tones on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. Just like Japan’s U.S.-inspired Ametora style influenced the United States for decades, this Japanese sneaker line cross-pollinated with the U.S., changing footwear irrevocably along the way.

Kith

What served as the true germination for CO.JP were shop-exclusive SMUs (special makeups). In the ‘90s and early ‘00s, Nike sales reps in the U.S. and Japan would often let shop owners request custom shoes. “That’s how these regional exclusives started – buyers from U.S. stores like Jimmy Jazz who were doing tens of millions of dollars of business a year with Nike,” said Staple. “Say you’re a buyer and you’re like, ‘Hey, I want this shoe, but I want it in all red. If you do it in all red, I’ll order 10,000 pairs.’ Nike sales reps would be like, ‘F*ck, let me call up Beaverton and get these pairs made so I can get an order.’ That’s not a quote-unquote collaboration [the way we see it today], but it kind of is.”

The ‘90s through the beginning of the new millennium was a vastly different time in the world of footwear. “Collaboration” was a mere whisper on the lips of footwear brands. Sneaker collecting was still largely an underground, regional subculture, brought together globally by a close-knit, intricate web of die-hard collectors who used forums like NikeTalk to buy, sell and trade, and spent endless hours scouring eBay for rare products. It was fertile ground for a cultural evolution, bolstered by knowledge, deep passion and the thrill of the hunt — something a collector had to commit to fully in the days before social media made the world of sneakers feel a lot smaller, and rare kicks could be yours with just a few clicks. Only a handful of footwear aficionados in New York and Tokyo knew about these “shop exclusives” — as they weren’t marketed by Nike — and even fewer had the means or the know-how to acquire them.

One of the main players acquiring U.S. store-exclusive SMUs was atmos founder Hommyo Hidefumi. As he told HYPEBEAST‘s Business of Hype podcast, Hidefumi would drive from Philadelphia to Boston and back, snapping up as many exclusive or retro pairs of Air Force 1s, Dunks or Air Jordans as he possibly could, and flip them to an adoring Japanese market for absurd profits — he’d typically pay $20 to $30 USD a pair and net more than 10 times that in Japan through Chapter, a store he operated before opening atmos.

What Hidefumi was doing in the U.S., other early resell entrepreneurs were doing in Japan. “[A small portion of the U.S. audience] was aware of CO.JP,” says Staple. “A store on Lafayette Street in New York named Clientele carried some styles, and a man named Damany started an eBay account called Vintage Kicks USA that eventually evolved to become Flight Club. There was another OG named Sonny Lam — these guys were basically power eBay sellers — and they had the means to get to Japan and bring back crates of kicks to flip on eBay or at stores like Clientele. Of course, Hidefumi was doing the opposite: he was coming to America driving up and down I-95 from Boston to Baltimore, picking up U.S. exclusive makeups and shipping them back to Japan.”

Hidefumi’s curated selection at Chapter opened up an entirely new world of possibilities. Nike’s Japanese employees would often stop by Chapter to bolster the company’s archives, and during this process Hidefumi was introduced to Marcus Tayui, the man in charge of Nike Japan’s “Energy” marketing, who was tasked with increasing the Swoosh’s cultural cachet by tapping local creatives and retail outposts for special makeups of classic models.

Sbd

“Marcus Tayui was the one guy at Nike Japan who was really pushing [shop exclusives] early,” says Staple. “He’d be like ‘Hmm, Kukinis … these are interesting. Let me let Hommyo Hidefumi take a stab at these, he’ll sell 24. Air Woven — these are interesting. the big boys aren’t gonna carry these, but let me send 72 pairs to another shop and see how it goes. And oh, Hommyo, if you’re interested in these Air Max 1s, do you want to put your own color spin on them?’ This was all before CO.JP was ‘officially’ launched.”

After Hidefumi opened atmos’s first store, these shop-exclusive releases fully evolved. “Hommyo and atmos were a little more curated and considerate about their exclusives,” states Staple. “With Japanese culture, everything has to happen for a real reason, not just the money. The project between Hommyo and Marcus was essentially a sub-line, where the shop owners in Baltimore, Boston and New York who were also getting their own SMUs didn’t have the wherewithal to create a line — they just did the exclusives.”

I asked Marcus,‘How do you know that the Zoom Spiridon’s the one, the Air Kukini’s the one, the Air Woven’s the one? How do you know what’s gonna be the special shoe? He said that he’d often touch base with a guy to determine what’s hot and what’s not. That guy was Hiroshi Fujiwara.

Tayui knew just who to look to for advice too. In 1998, Staple was the creative director of The FADER, and traveled to Japan for a now-legendary feature article on the trans-Pacific desire for rare sneakers. “I asked Marcus, ‘How do you know that the Zoom Spiridon’s the one, the Air Kukini’s the one, the Air Woven’s the one?’” said Staple “How do you know what’s gonna be the special shoe? He said that he’d often touch base with a guy to determine what’s hot and what’s not. That guy was Hiroshi Fujiwara. This was pre HTM, pre fragment design x Nike, pre everything.”

From then, it was off to the races. The ‘00s saw the germination of the seeds planted by SMUs exclusives and relentless collectors. One of the first times that the product crossed the ocean at Nike’s behest instead of collectors shipping crates of kicks was via New York’s Alife, who helped bring the Air Woven from Japan to New York’s Rivington Street. Alife even had famed artist and fellow Nike collaborator Espo tag the underside of each pair’s insoles — a secret revealed by founders Rob Cristofaro and Treis Hill in a Business of Hype episode. CO.JP then began spreading globally, serving as a precursor to Nike’s ultra-limited Tier Zero drops. “One store per city — Footpatrol in London, colette in Paris,” says Staple. “Nike said, ‘Let’s give them these CO.JP shoes so it’s not just Japan that’s getting them, it’s the highly regarded stores around the globe.’”

Nike

Marcus Tayui forecasted this shift when speaking to Staple for FADER in 1999.

“We sell those shoes to maybe one to 17 [shops in Japan]. It’s really exclusive energy shops so we don’t put the shoes in sporting goods shops or department stores. [We’re] really focused on accounts that have a lot of street credibility. [Our products are] not geared for everyone, just what we consider ‘inner city’ accounts. And naturally, the trends and movements in Tokyo are so fast that even our energy accounts are constantly shuffling,” Tayui said at the time.

“We try to focus on stores with good concepts, stores that are high fashion, on the edge or produced well. We have stores that celebrities own, we have stores that skaters just got together and started, like Supreme. We try to tie up with those fellas and get them involved — not really in production and design, but in coloring shoes. That and natural product marketing,” he added.

Sneakers Delight

Sound familiar? It should — it’s the blueprint for any and all of today’s footwear collaborations. Pull a sneaker with a story from the archives, then let a culturally significant entity give it a fresh personality and use their cultural cachet to market it. It’s a tried-and-true method that’s now been running for two decades strong, but found its seeds through CO.JP.

CO.JP was the genesis of much that the modern sneaker lover is familiar with: quickstrike releases, Tier Zero marketing, shock drops, Hiroshi Fujiwara-adjacent footwear. You could even make the case that CO.JP’s eBay “power sellers” kicked off modern reselling as we know it. Not only that, but it also provided the roots for one of the world’s biggest premium boutique chains (atmos) and aftermarket operations (Flight Club).

Much like its origins are shrouded in mystery, CO.JP’s “end” is somewhat muddled as well. The line was never officially “discontinued” but its releases slowed to a trickle and then stopped by the time the 2010s rolled around. A question arises: is CO.JP a relic of the past that has largely served its purpose, or could it see a revival in today’s fully globalized world of footwear? Staple sees it as the former.

“The first thing that comes to my mind when I think of CO.JP is the hunt.”

“The first thing that comes to my mind when I think of CO.JP is the hunt,” he says. “To learn about this product and its story, I had to hop on a plane, go to Japan. How do you get these experiences now? What’s memorable about outbidding someone for a pair online and receiving the kicks at your home? There were real life experiences, and with CO.JP, there were the disparate experiences of Tokyo and New York. If Nike ever does decide to bring back CO.JP, they should bring the experience making back into the product.”

Although it’s no longer at the forefront, CO.JP DNA is indeed alive and well. KITH head Ronnie Fieg acknowledged the initiative as a source of inspiration behind the KITH x Nike Air Force 1 that released to celebrate his Tokyo store opening. The Air Jordan 1 “Japan/Metallic Silver” has returned with its original metal briefcase. And the Japan-exclusive Air Jordan 3 “Denim” even has CO.JP printed on its insoles.

CO.JP’s influence won’t always be seen — but it will always be felt and appreciated, no matter how much the world of footwear’s paradigms shift.

The Link LonkAugust 07, 2020 at 08:48PM

https://ift.tt/2PzTAaZ

Nike's CO.JP Line Laid the Blueprint For Modern-Day Sneaker Collecting - HYPEBEAST

https://ift.tt/3g93dIW

Nike

No comments:

Post a Comment